Apollo 11 landed on the moon July 20, 56 years ago this week. I was 19 years old, home from college for the summer. Just south of Mt. Pleasant, Iowa was a rock quarry filled with water where kids often gathered. There were no lights for miles. We weren’t supposed to be there, which made it all the more appealing. On that night, I remember sitting on a rock moon-gazing. My dad was home in our back yard watching, too. As a naval aviator during WWII, he navigated by the stars.

When I was a little girl, he told me that the moon was made of cheese and showed me how to find the man up there. Over time, and with the help of a telescope, he taught me to love the night sky, identifying the North Star and other navigational stars like Vega, Altair and Deneb. Once he woke me in the middle of the night to see the Northern Lights. We watched Sputnik, then Explorer, passing through our summer sky, harbingers of moon visits to come.

Our fascination with the night sky was enhanced, because scientist Jim Van Allen had grown up in Mt. Pleasant and was a friend of our family. Dr. Van Allen had put scientific research instruments on space satellites including Explorers 1 and 3. As a result, he discovered radiation belts that are named for him. Time Magazine featured him on the cover in 1959, and the article read, “No human name has ever been given to a more majestic feature of the planet Earth.”

REGARDS TO THE MEN IN THE MOON

That night at the quarry was magical, but I also understood that the world had changed. No, the moon was not made of cheese, but there was a man there, two in fact, and their names were Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. There are streets named for them in my hometown and a school named for Dr. Van Allen.

So often, we remember, and history records, the dates of wars beginning and ending, terrorist attacks or assassinations. But that week, for those of us who remember it, was unique for a life-changing experience that celebrated one of humankind’s greatest achievements. President Kennedy never got to see the moon landing, but he inspired it. As Americans, we felt proud of ourselves. He encouraged American children to become physically fit, so that some of us could become astronauts, too.

Of course, at the time it was just men, but I imagine that night Sally Ride was also watching the lunar landing and out gazing at moon. She was a year younger than I and became the first American woman to fly in space on the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983.

SPLASH DOWN FOR COMMANDER PEGGY WHITSON

In 1981 Peggy Whitson, from small town Mt. Ayr, Iowa, came to study the sciences at Iowa Wesleyan College in my hometown where Dr. Van Allen had also attended college. Today Commander Whitson has been in space longer than any other American woman. She commanded the Space Station twice. Until, yesterday, July 15, she was orbiting 250 miles above us as Commander of the Axiom Mission Ax-4, a private space mission to the International Space Station. She and her crew splashed down off the California at 2:31 am. A few years ago, she returned to Mt. Pleasant to speak to a gymnasium full of 8th graders bussed in from surrounding schools. As someone who taught 8th graders for 20 years, I know this is a hard audience, but Peggy had them transfixed. I’m positive that more than one of those hundreds of students, all from small communities like the one she grew up in, left there thinking that they could be her, too.

And for those of us who will never go to space, because we don’t like to fly, because we are not proficient enough in science, because we aren’t physically fit, we can still be part of the magic. Dr. Van Allen never flew in space, but he made it possible for others to do so. In fact, he was not sold on human space flight and would be gratified to know we’re thinking about Mars.

When I last saw Dr. Van Allen in Iowa City, his 8-year-old granddaughter was visiting. I got a photo of the two of them sitting at a computer while she showed her grandfather how to log on. She didn’t yet know that his work pioneering scientific instrumentation contributed to data processing techniques that made the computer she was using possible.

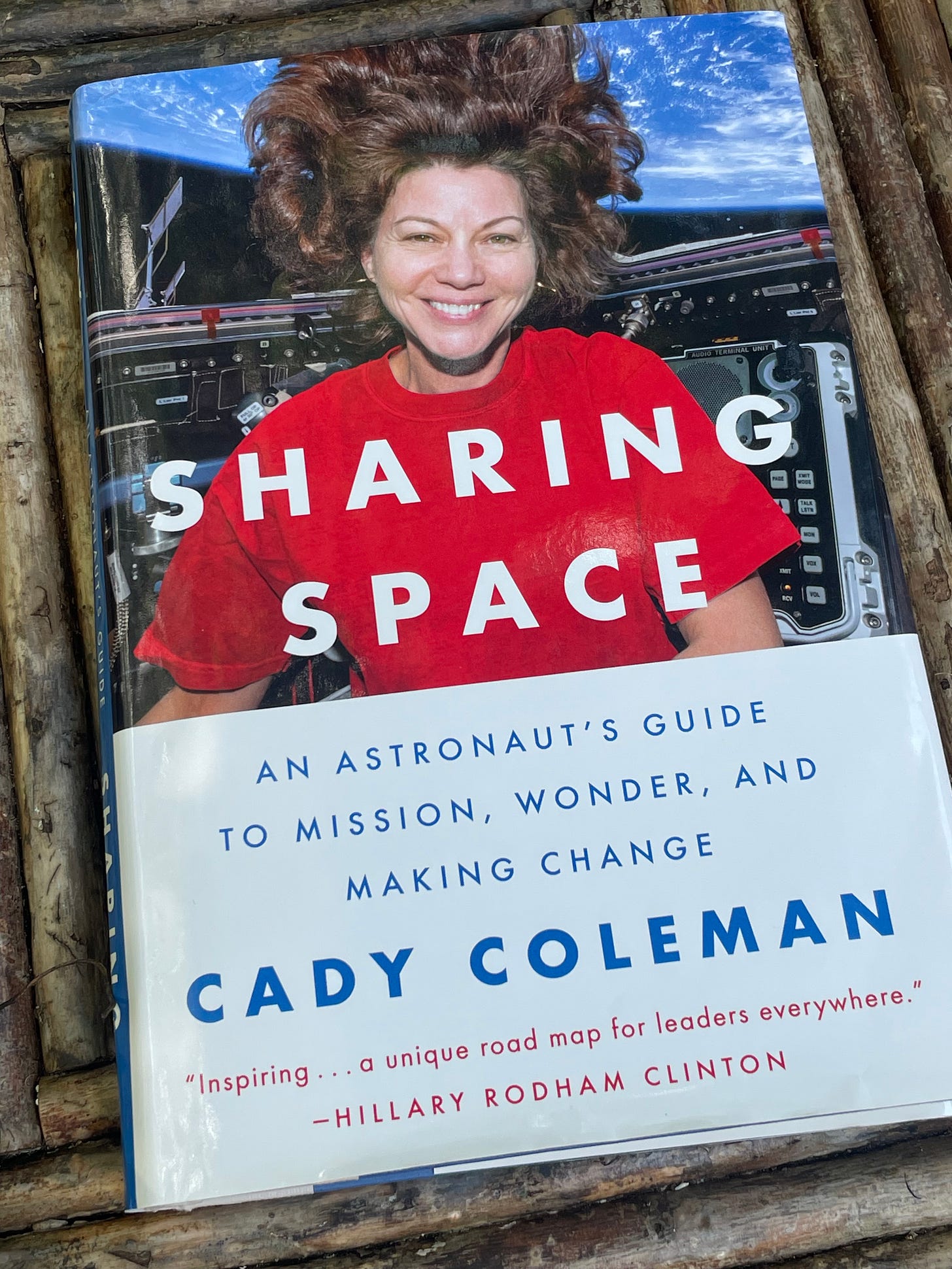

CADY COLEMAN, DEFYING GRAVITY

Others will let words and images capture the magic of space flight and the night sky. Samantha Harvey’s 2023 novel, Orbital won the 2024 Booker Prize. You can call it science fiction or literary fiction. I call it dessert, like a small, tangy piece of lemon meringue pie. In a few hours of reading, you can spend a week in space at 250 miles above the earth. You can bond with 6 astronauts from different counties and cultures and get a feel for the irony of living in a confined space in the most expansive experience known to humankind. You can feel their ebullience and their aloneness in the same paragraph. The language is so rich and yet so sparse. I marked sentences to read aloud to my book club just to hear how they sounded.

And yet, Orbital is fiction. Samantha Harvey did not travel to the Space Station. Cady Coleman did. So, if it’s a true story of space travel you want, try Sharing Space. This memoir captures the wonder of space flight but doesn’t mince words about how hard it was to earn astronaut status as a woman who didn’t follow a traditional path. Many of those choosing the teams she wanted to join along the way didn’t think she was qualified. Many didn’t understand how she could have a long-distance relationship with a husband and child, then leave them behind to live in space for months at a time. She explains how she led by creating a team in space as an extrovert among introverts. She writes about adapting to a space suit made for much larger men, because complaining would mean not getting the job. When Cady started working toward her goal, few, if any, would have believed that someday she’d become qualified to walk in space.

In April, she and her husband, Josh Simpson, a glass artist, spoke at the Brunier Art Museum at Iowa State University. They spoke about the synergy they create, and how their respective careers influence each other. We’ve known Josh since college days, so we joined them at the museum, which features Josh’s work in a permanent glassblowing exhibit. He specializes in blowing planets. As he travels the world, he drops his smallest glass planets in unlikely places for people to find and wonder about: beaches, the Great Wall of China, The White House.

THE BLUE MARBLE AND THE ARTS IN SPACE

If you really want to challenge the boundaries of our earth and universe, try watching the movie Gravity with Sandra Bullock and George Clooney or read Martin Macinnes’s in Ascension. The endings of both the movie and the book are open-ended, challenging the reader to engage in speculation, inspiring us to think beyond the current parameters of time and space.

In every aspect, space exploration can be inspiring at a time when inspiration seems hard to find. A naval aviator inspired my love of the night sky. Professor James Van Allen pursued a career in research and teaching that inspired another generation of scientists anxious to explore space. President John Kennedy inspired a generation of children to pursue science and to practice physical fitness so that when astronauts walked on the moon, we would feel a part of their success and aspire to walk there too or accomplish something equally unique.

INSPIRATION COMES WITH A PRICE TAG

Inspiration, though intangible, still comes with a price tag. In every instance I’ve mentioned, inspiring the next generation meant that we as a nation had to invest in educators, in research and in research institutions. For instance, it meant expanding investments in the military to include women.

Going forward, the price of Inspiration means supporting iconic government programs like NASA while partnering with private investors in research and space exploration. It means creating STEM opportunities in libraries and schools and hosting space camps. It means encouraging high school and college graduates to join the military as a portal to the space program. Inspiration means supporting the reporting about and oversight of our investment in space. It means supporting the artists who want to capture awe-inspiring images, like the Blue Marble, one of the most reproduced imagines in history. Inspiration means inspiring scientific exploration of growing food in space, one of Commander Peggy Whitson’s specialties.

Sometimes we can quantify inspiration and sometimes its elusive. Investing in a model rocket kit for a child or buying a subscription to Popular Mechanics for the local library, supporting programs that send scientists like Cady Coleman and Peggy Whitson to speak at schools and museums may seem like the kind of programs that can easily be cut, but these are investments worth making, if we care to take the long view. As a life-long educator and a stargazer I’m for taking the long view into the future.

As always, your writing is lovely 🥰 and a joy to read! My dad also raised me in Iowa, and we probably have more in common than might be thought. My dad was a genius and quite gifted.

Grand Prairie, TX, with new wife and visiting-from-Iowa parents in attendance, on a rented-for-the-occasion B&W TV. Deployment to RVN six days later seemed anticlimactic.